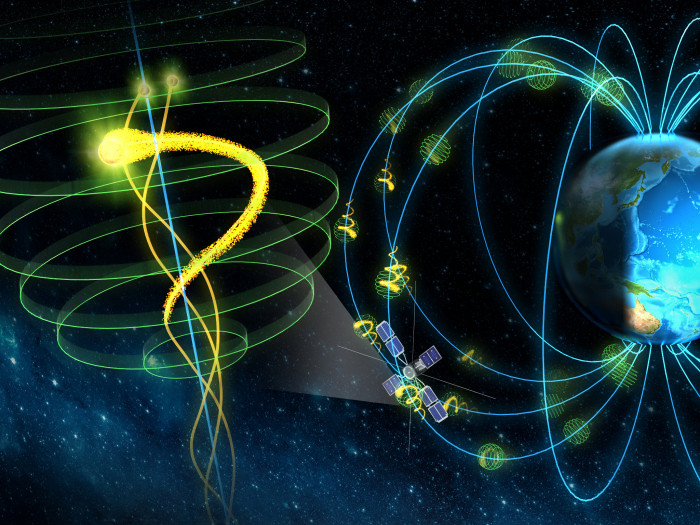

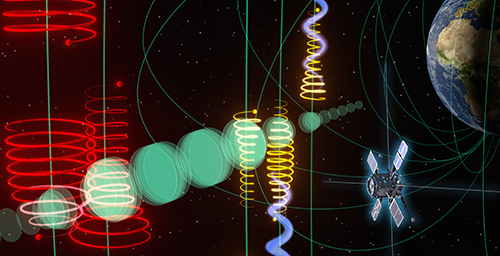

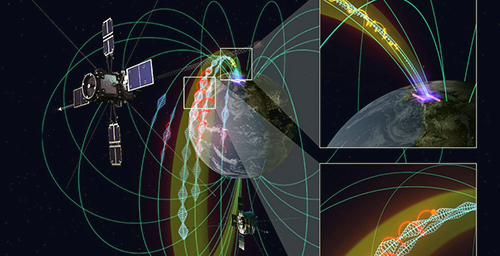

Image of traces of ultrafast electrons acceleration caused by plasma waves by the Arase (ERG) satellite(© ERG science team)

Summary

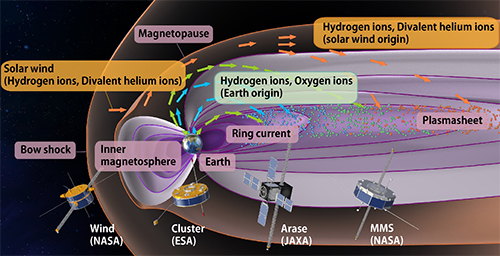

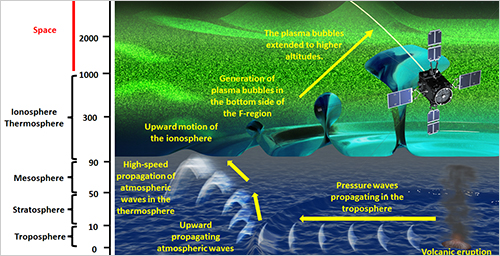

The vicinity of space surrounding the Earth and that of other planets is filled with plasma that exists at a variety of energies, from low values of less than one electron volt that are found in the upper atmosphere, to high-energy plasma that exceeds one mega-electron volt within the Van Allen radiation belts. This diversity in energy is thought to originate from the interaction between spontaneously occurring plasma waves in space and the charged particles that compose the plasma.

Extensive theoretical research aimed at explaining this energy diversity has proposed a process in which the charged electrons gain energy from a type of plasma wave known as a chorus wave (often called birdsong in space)*. The energy transfer from the chorus wave occurs over a very short time, allowing the electrons to be rapidly accelerated in less than one second. Until now, observational evidence of this process has been challenging as the performance of particle detectors has been insufficient. However, by applying a new analysis method to the high-quality observational data from the Arase (ERG) satellite, we have identified evidence of chorus waves accelerating electrons on sub-second time scales for the first time in the world. Chorus waves are present around planets with radiation belts, such as Jupiter and Saturn, and this acceleration process is expected to also occur around these worlds.

This discovery marks the first empirical observation of the rapid electron acceleration process caused by chorus waves operating in space. It is an exciting achievement that will help clarify how high-energy electrons are generated around the Earth and other planets.

Background

The space surrounding the Earth and that of other planets is filled with plasma, but the density of that plasma is so low that collisions between the charged particles are rare. An electron with a given amount of energy therefore will not lose this energy through collisions with other ions or electrons, nor gain energy from such interactions.

Seemingly contrary to this, the plasma surrounding the Earth has two primary sources: the upper atmosphere, where electrons typically have energies of less than one electron volt, and the solar wind, where electron energies range from about ten to several hundred electron volts. Yet, within our planet's magnetosphere, there are a wide range of electron energies that span from the kilo-electron volt range into the mega-electron volt range. The number of electrons at these wide range of energies fluctuates dramatically. To understand this variation in energies, a mechanism for energy exchange and motion must therefore exist that does not involve particle collisions. One option is that such variations are mediated by "plasma waves", which are electromagnetic waves that spontaneously generate in space, and these waves drive the dynamic changes in the energy of electrons and ions in space.

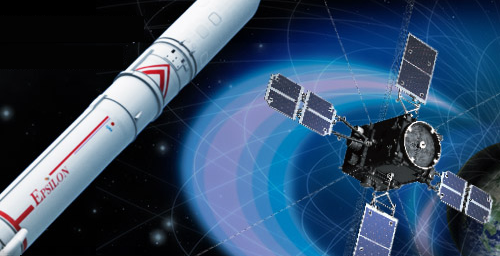

The Arase (ERG) satellite was launched in December 2016, with one of its primary objectives being to clarify the mechanisms behind the repeated generation and loss of radiation belts. Radiation belts are regions filled with highly energetic electrons that surround the Earth. In order to measure particles across a broad energy range that extends from tens of electron volts to several tens of mega-electron volts, Arase is equipped with a number of particle detectors that are each suited to different energy levels. For observations of radio waves, Arase is also equipped with multiple receivers capable of precisely measuring a wide range of frequencies from direct current (DC) to 10 megahertz. The combination of the particle and radio wave instruments allows the collection of world's highest quality data to investigate the space environment around the Earth.

With this data from Arase, we were able to clarify that the electron acceleration process--predicted to occur between electrons and chorus waves in less than one second--is occurring in space. The acceleration timescale mentioned here is significantly shorter than the several to tens of minutes predicted by quasi-linear theory, which has been widely discussed for many years. This new work also confirms a value significantly shorter than the limit on the acceleration time that was identified in our previous analysis of the observational data from Arase, which was found to be less than approximately 30 seconds [Kurita et al., 2018].

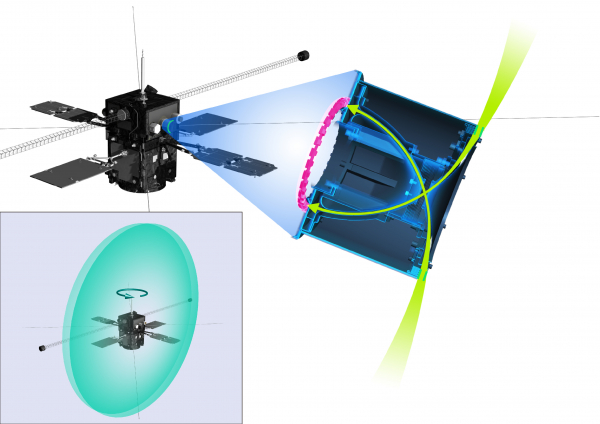

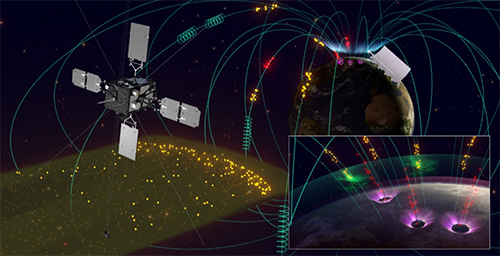

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of the MEP-e instrument installed on Arase. The lower left figure shows the relationship between the spin direction of Arase and the disk-shaped field of view of MEP-e. (© ERG science team)

Results

Theoretical considerations suggest that the rapid acceleration of electrons by chorus waves selectively accelerates only those electrons that meet specific conditions. The change in energy of electrons that do not meet those conditions is assumed to be much smaller. As these conditions for rapid electron acceleration is not always satisfied, an intermittent surge in the number of electrons is expected when conditions are temporary fulfilled and this rapid acceleration occurs.

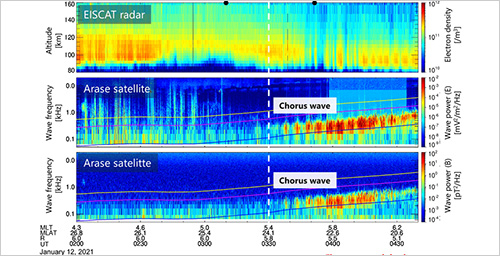

As the time scale necessary for electron acceleration is believed to be less than one second, analyzing electron count measurements with high temporal resolution is essential to confirm this acceleration process. This resolution is achieved by using data collected every 250 milliseconds by the Medium-Energy Particle experiment (MEP-e) onboard Arase, as well as data from the Plasma Wave Experiment (PWE) and Magnetic Field Experiment (MGF) instruments, variations in the electron number associated with the appearance of chorus waves within one second were successfully detected.

MEP-e is an electron analyzer with a disk-shaped field of view, and designed to measure the entire field of view by utilizing the rotation of the satellite that takes approximately eight seconds (see Figure 1). In order to obtain detailed information about the direction of electron arrival, the measurement during a single rotation of the satellite is divided into 32 spin phases, and electrons with 16 levels of energy are measured in each spin phase. With the MEP-e data acquisition method, the number and direction of arriving electrons at a specific energy can be determined approximately every 250 milliseconds (about 8 seconds divided by 32 spin phases). One important point to note is that due to the relationship between the rotating disk-shaped field of view of MEP-e and the orientation of the Earth's magnetic field, measuring electrons with small pitch angles (the angle between the Earth's magnetic field and the electron's velocity) may not be possible. However, theories of rapid electron acceleration expect that the accelerated electrons will exhibit a larger pitch angle, and so the influence of the spin dependence on the field of view is reduced. This makes it possible to apply the analysis using the MEP-e data with the higher time resolution.

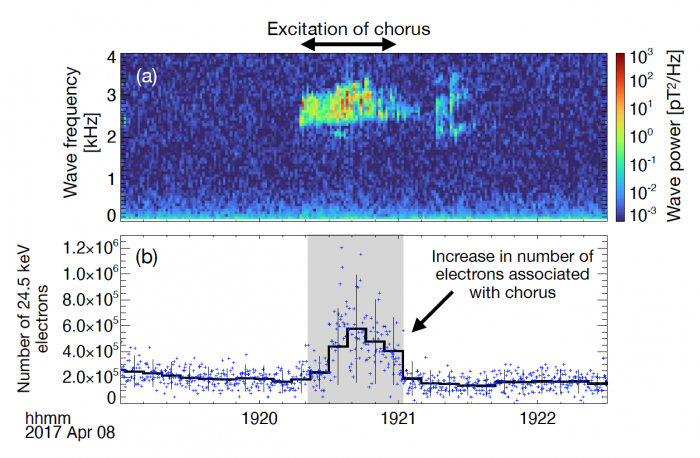

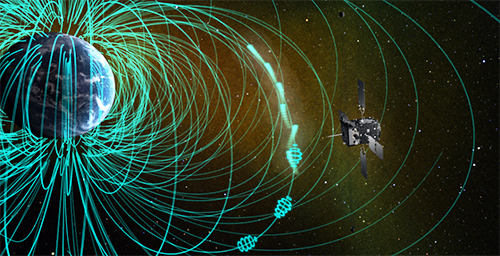

Figure 2: Short-time electron acceleration associated with the chorus waves observed by Arase. (a) Dynamic spectrum showing the variation of the wave strength versus time and frequency. (b) Electron number fluctuations at 24.5 kilo-electron volts, with the number of electrons every 250 milliseconds shown as blue dots, the average over the satellite spin-period (~8 s) is shown as black lines, and the data variance (standard deviation σG) over one spin is shown as vertical lines. (Modified from Kurita et al., 2025)

Figure 2 illustrates the frequency spectrum of the chorus wave observed on April 8, 2017 at about 19:20 UTC (Figure 2a), and the number of electrons observed by MEP-e (Figure 2b). In Figure 2b, the 24.5 kilo-electron volt electron count over a pitch angle range of 60-80 degrees is shown every 250 milliseconds (blue dots), overlaid with the average electron count over the satellite spin period (~8 seconds) which is commonly used in analyses (black line). The number of electrons can be seen to be increasing at the same time as the appearance of the chorus wave is observed. Here, the electron count at 250 milliseconds resolution shows more significant time variations during the onset of the chorus wave than before and after its disappearance, with certain values considerably exceeding the averaged value over eight seconds. This observation is consistent with the electron number variation expected from the theory of rapid electron acceleration by chorus waves.

Figure 2b also shows the standard deviation σG as vertical lines, which indicates the extent of the variation in the number of electrons observed every 250 milliseconds with respect to the eight second average over the spin period. The scatter in the data increases with the onset of the chorus wave.

While Figure 2 showed visual agreement between the onset of the chorus wave and electron acceleration, a quantitative measure was needed to assess if the scatter seen in the MEP-e results was due to the chorus wave rapidly accelerating the electrons, or variations due to measurement uncertainties. To compare to the value of σG, the measurement uncertainty was calculated as the square root of the particle number to give a second standard deviation, σP. The uncertainty in the particle measurement therefore increases by the square root of the particle count as the number of particles rises. σP shows good agreement with σG as the particle number becomes large. To distinguish whether the scatter in the MEP-e results is due to measurement uncertainties or due to the chorus wave accelerating the electrons in a very short time period, variation coefficients were evaluated, which are the standard deviation of the particle number divided by the number of particles. Since the variation coefficient calculated from σP is proportional to the inverse of the square root of the number of particles, it decreases as the number of particles increases. Additionally, the nature of σP means that the variation coefficient is expected to approach the variation coefficient calculated from σG as the number of particles increases. Therefore, where the variation coefficient calculated from σP shows a different trend compared to the variation coefficient calculated from σG, we can conclude that the measurement at 250 milliseconds is influenced by short-term fluctuations in electron numbers caused by the chorus waves.

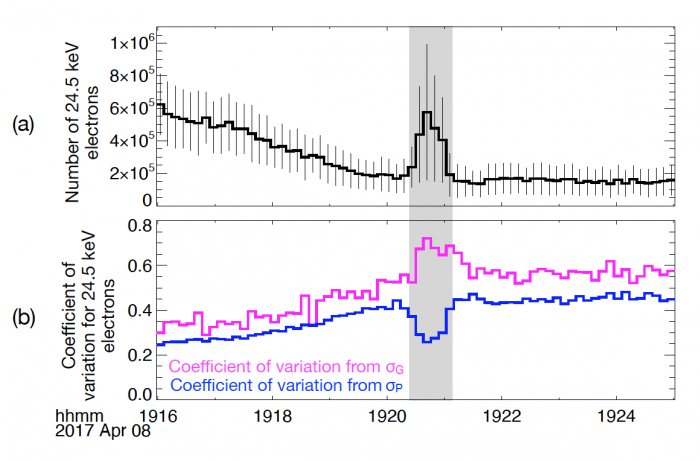

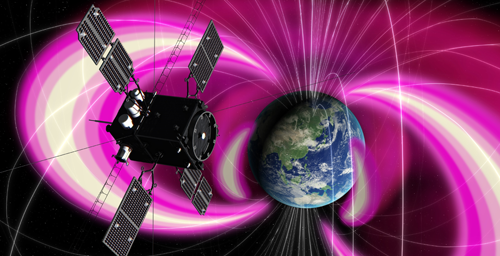

Figure 3: Time variation of the variation coefficient associated with the onset of electron acceleration by the chorus. (a) Spin-period average and standard deviation σG of the electron number at 24.5 kilo-electron volts. (b) Time variation of the variation coefficient of the number of electrons at 24.5 kilo-electron volts. Magenta and blue lines indicate the variation coefficients calculated from the standard deviations evaluated with different methods, respectively. (Modified from Kurita et al., 2025)

Figure 3 shows the change in the variation coefficients associated over the period of time when the electrons are being accelerated by the chorus wave. The variation coefficients calculated from σG and σP generally show similar time variations before and after the electron acceleration is triggered by the chorus wave. However, when the number of electrons increases, the variation coefficient calculated based on σP decreases. In contrast, the coefficient of variation based on σG increases when the number of electrons increases. When the variation coefficient based on σG is calculated over the distribution of electron energy and the direction of arrival relative to the magnetic field lines, it was found that the value increases in a specific region of the electron energy-pitch angle distribution compared to that based on σP during the time when the number of electrons increases rapidly. This region aligns well with expectations of increased electron numbers due to the chorus-induced rapid acceleration theory. The results indicate that the Arase observations provided evidence of short-term electron acceleration caused by chorus waves.

Future Prospects

This study has revealed that rapid electron acceleration caused by chorus waves, which was previously only theorized, does occur in space. This phenomenon rapidly increases the number of high-energy electrons within a time frame of less than one second. It has been theoretically predicted that this acceleration process contributes not only to the production of electrons with energies ranging from a few kilo-electron volts to around 100 kilo-electron volts as measured by MEP-e, but also may generate electrons with energies in the mega-electron volt range that are responsible for forming the radiation belt. The new analysis method presented here focuses on the variation coefficient, which is applicable not only to MEP-e, but also to particle detectors onboard current and previous satellites that have been conducting observations in space, making the technique highly versatile. Using this method on past satellite data can help to clarify the energy transfer processes of electrons and ions caused by plasma waves. However, it is important to note that a sufficient number of particles must be counted within a short timeframe to conduct this analysis, which was possible for this study due to the high sensitivity of MEP-e.

Chorus waves has been observed in space in the vicinity of the Earth, as well as around the outer planets, such as Jupiter and Saturn. The chorus-induced short-term acceleration process likely contributes to the production of electrons with energies exceeding one mega-electron volt around these planets. The existence of a chorus in Mercury's magnetosphere is also strongly suggested by observations during the swing-by of the BepiColombo/Mio mission. By applying the method proposed in this study to the observation data that will be collected after Mio is inserted into Mercury's orbit, we believe it will be possible to investigate the existence of ultrafast electron acceleration by chorus waves in Mercury's magnetosphere.

The MEP-e onboard Arase has collected dozens of events of chorus-induced electron number fluctuations with a time resolution of 8 seconds. Applications of this analysis method will give a deeper understanding of the short-time electron acceleration process due to chorus waves.

*A chorus wave is an electromagnetic wave that travels through plasma-filled regions of space. It is commonly observed around Earth and propagates easily along magnetic field lines. These waves can be detected at frequencies ranging from a few hundred hertz to a few kilohertz, which falls within the range of human hearing. The name comes from the fact that when the chorus signal is converted to sound, it sounds like birds chirping.

Paper Information

Title of paper:Detection of ultrafast electron energization by whistler-mode chorus waves in the magnetosphere of Earth

Authors:S. Kurita, Y. Miyoshi, S. Saito, S. Kasahara, Y. Katoh, S. Matsuda, S. Yokota, Y. Kasahara, A. Matsuoka, T. Hori, K. Keika, M. Teramoto & I. Shinohara

Journal:Scientific Reports